Posted on 20th June 2022 by Media Relations

The long, tall journey of giraffe conservation in Northwest Namibia

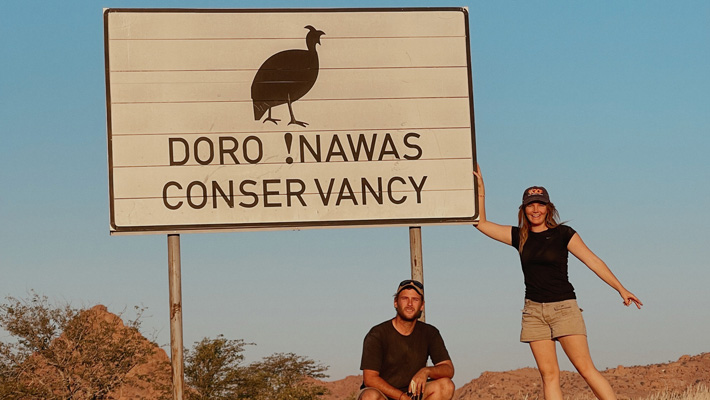

By Lachlan McFeeters and Jordan Michelmore, GCF Field Researchers – NW Namibia

North-western Namibia is one of the last remaining ‘wild places’ on the planet. The rugged and unrelenting landscape has an aura that captures the imagination of photographers, geologists and wildlife enthusiasts alike, with unspoilt vistas, baffling rock formations and uniquely adapted species around each turn. This arid environment is a wash of dry earthy tones, only broken for a moment, by a giraffe awkwardly probing its nostrils with a bright purple tongue.

Conserving Namibia’s desert-dwelling giraffe is one of a number of conservation initiatives of the Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF), and it is the longest running ecological monitoring effort of giraffe in Africa. It is a privilege to run such a program, and working alongside like-minded, dedicated and inspiring conservationists has driven our journey from Australia to remote NW Namibia.

GCF is the only organisation in the world that concentrates solely on the conservation and management of giraffe in the wild throughout Africa. GCF currently works on, manages and supports giraffe conservation initiatives that concern all four species of giraffe in 17 African countries. The work of the small but dedicated team has an impact on over 100 million acres of giraffe habitat.

The North-west Namibia Programme is a comprehensive population analysis of Angolan giraffe in the Kunene region. Our best estimate is that there are about 15,000 giraffe in Namibia, with 434 of them inhabiting the arid to semi-arid, isolated river networks that meander their way down the north-west of the country. Giraffe don’t just survive in this rather hostile space, they thrive and capitalise on the moisture provided by the vegetation that lines these predominantly dry riverbeds.

The backbone of this long-term conservation research project was the desire to develop a greater understanding of how giraffe use their environment and navigate the pressures of such a unique landscape. Results will provide vital insights into the social dynamics of giraffe populations and add to the narrative of their behavioural nuances, feeding strategies, resource and habitat usage and other relatively unknown information. This will have wide reaching conservation benefits, as GCF implements strategies to safeguard giraffe populations in Namibia and throughout an additional 16 countries.

The study area covers around 30,000 km2and comprises a mix of communal conservancies, nature concessions and the northern stretch of the Skeleton Coast National Park. The ephemeral river systems meander through the landscape providing sustenance in an otherwise barren environment. The stark presence of vegetation supports a host of desert adapted species from large browsers like elephants and giraffe, to grazing oryx and mountain zebra and the formidable carnivores that have adapted to the unrelenting arid conditions.

It would be impossible to compare this landscape to anywhere else on the planet; an awe-inspiring accumulation of endless flat plains, stunning outbursts of granite and the powder-like sand which unifies these unique features. The abundance of species is impressive to say the least, but to see them exist in this geological paradise is an astounding triumph for such an ecosystem.

Giraffe numbers in the area dwindled in the late 80s following the Namibian Independence War and were again supplemented through translocations of a few individuals in the early 90s. With the formation of communal conservancies in the region including the Puros, Sesfontein, Sanitatas, Orupembe and Okondjombo conservancies, local communities demonstrated how wildlife and people can co-exist successfully in self-managed open habitat.

Our surveys concentrate on three main river systems; the Khumib, Hoarusib and Hoanib rivers, as well as their many tributaries. We spend the best half of each month manoeuvring through the landscape, identifying and recording each individual giraffe using ID books consisting of left and right photographs of all 434 giraffe. Each animal is identified by their unique coat pattern, and we record a number of observations including herd structure, location, reproductive status and any other noteworthy data. Over time, this will enable us to understand aspects of their ecology including the seasonal variations in their movements, how far giraffe wander, why movements differ between individuals in different systems, and the intricacies that make up their fission-fusion social structure.

This analysis can then be compared to other giraffe populations in other parts of Africa and provide an exciting opportunity to broaden our understanding of one of the world’s most iconic animals.

With their striking coat pattern, tall stature and unique morphology, giraffe should be a distinct inclusion in the environment. However, they can be tricky to spot. Their coat pattern helps them blend almost seamlessly into the mottled shade of their preferred vegetation, and their spindly legs can easily be mistaken for low branches after a couple of weeks in the desert sun. Their presence may be obvious at times, but occasionally only given away by a flick of their tail, a slight ear flick or a ruminating stare protruding from above a Salvadora bush.

One of the many satisfying aspects of the project is the opportunity to connect people with these awkwardly elegant creatures. To see a giraffe confidently traverse wind-swept sand dunes and carefully navigate thorned acacia branches is a great privilege, and to contribute to our understanding of Angolan giraffe while doing so makes for an unrivalled opportunity.